As summer approaches, I’ve been having a lot of conversations about heat. Some are more casual comments, lamenting how hard it feels to hike in hot weather. Some are partners’ more serious accounts of tending to heat stroke. Both made me wonder about how our bodies respond to heat, and how a deeper understanding of my own physiology can help maximize my performance, stamina, and safety throughout the summer. Here’s what I learned:

- There’s a reason exercise is harder when we’re hot. It’s common knowledge that when our bodies are cold, our blood vessels constrict in our extremities and we keep more blood in our core. But the reverse is also true. When our body temperature gets hot, we send more blood up to the surface of the skin because, for several reasons we’ll get into below, our skin keeps us cool. In order to circulate all that blood, our hearts beat faster, and we breathe heavier just by walking outside. It adds more stress to the body compared to a workout in comfortable temps. Hydration is also crucial to this process – it’s not just creating sweat. When it’s hot, our bodies need that water to create plasma (the liquid part of our blood) so that blood can flood into those skin-surface capillaries and dump heat. If you get red or puffy while you’re working out in the heat, it’s just a sign your body is doing all the right things to cool you down. Heat emergencies and heat fatalities occur when our body temperatures get too high and to the point it overwhelms the cardiovascular system or diverts too much blood from other vital organs. Also, part of the reason we treat heat illnesses by icing someone’s neck, armpits, and groin is that those are places where major blood vessels travel close to the surface of the skin.

- Hydration isn’t just to create sweat. We’ve determined that hot bodies pump a lot of blood and push it into our skin-surface capillaries to dump heat. In order to do that, we need a lot of blood (or more specifically, the liquid part of the blood called plasma, which is 90% water).

- Heat adaptation takes time. We need to stay hydrated to produce plasma, but that adaptation isn’t immediate. It takes a few days to generate more plasma. But once you get more plasma, you have a lower concentration of hemoglobin to carry oxygen around, so our kidneys create more hemoglobin. It takes 1-2 weeks for our bodies to fully acclimate. This is also why you see heat advisories for temps in the 90s in the PNW or New England, but not in Texas or Arizona. It’s both about trends and norms as well as overall heat.

- Skin is really cool. The body uses evaporation to keep skin cool in hot weather. Don’t ask me to explain the intricacies of thermodynamics (I was a psyc major after all). But it takes 580 cal/gm of energy to convert sweat to vapor at skin’s normal temperature (energy calories, not food calories). That energy comes from our body heat, and in turn, keeps the surface of our skin cooler. Our bodies also gain or lose heat from conduction (sitting on a cold rock), convection (wind chill), and radiation (being in direct sunlight).

- It’s not the heat, it’s the humidity. So if evaporation is how the body stays cool, you’ll stay cooler when water evaporates more readily. In a dry environment, there’s a lot of “room” for water vapor. But when it’s humid, sweat tends to just sit on the skin where it’s not providing the same cooling benefit.

- Thermodynamics interact with the rest of our environment too. We know that a forested trail will feel cooler than an exposed hike above treeline. Part of this is an obvious benefit of shade, but plants kind of sweat like us, in a sense. They use water and the energy from heat in transpiration. In cities, vegetation can cool things down by up to 3F degrees. I’d gander that trees have an even bigger impact in a proper forest. Hiking by water also makes a difference. Water has a high “specific heat capacity,” which means it takes more energy to heat water than it takes to warm dirt and rocks. While land gets hot and heats the air above it, water doesn’t warm the surrounding air as dramatically. That temperature delta also helps generate wind, which in turn cools our body through convection.

So what does this mean for summer hiking?

- Thermoregulation is a health issue. First and foremost, trust the health pros. Before delving into any hot weather hiking tips, note that none of these supersede guidance from your doc, especially if you have any health issues that may relate to your heart, lungs, or kidneys.

- Ease into the season. Heat tolerance builds over a few weeks, so take the first few hot days of the year and start small. Keep time somewhat brief. Stick to gentle, easy movement like walking or gardening, and slowly build time and intensity.

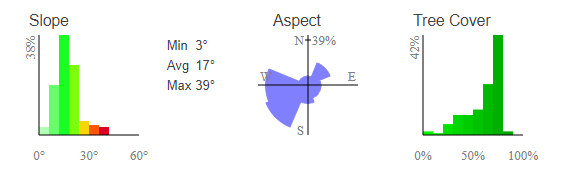

- Pick a trail using CalTopo. CalTopo has some really cool mapping features, like showing sun exposure, tree cover, and trail grade. Pop into “Map Objects” (or hit ctrl+o), click add, select line, and trace the trail you’re interested in hiking. Click the finished line, select Terrain Stats, and it’ll show you how the elevation change is dispersed throughout the hike and how much shade you can expect on the trail. For slope, on hot days, I look for almost exclusively green and lime terrain. Some newer hikers or heat-sensitive folks might want to look for graphs showing flatter / more gradually climbing terrain. For the Tree Cover graph, 100% coverage means views of the sky are completely blocked off for that section of trail.

This screengrab is from yesterday’s hot weather hike to Lake Margaret:

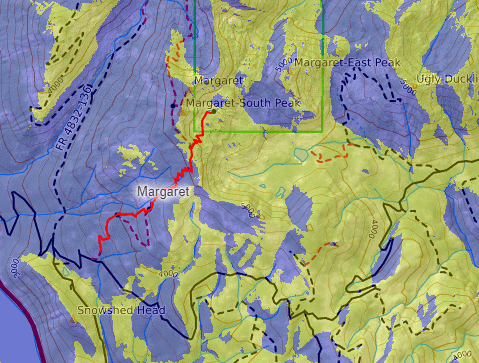

CalTopo has a separate feature for sun exposure in the Map Layers (hit ctrl+l to open the menu). Select the “Sun Exposure” layer, and you can see if the trail’s in direct sunlight over 30 minute increments. The screenshot below is the sun exposure for the Lake Margaret Trail at 7am. It starts getting sun between 7:30 and 8 and stays sunny til 9pm. Meanwhile, Thorp Lake to the east gets sunny by 6:30am, and Annette Lake stays shaded until almost 9am. There’s nothing worse than waking up early to beat the heat, only to pick a trail that’s roasting shortly after sunrise.

- Use Windy to optimize the weather. I start my weather planning with Windy. It’s not the most sensitive weather tool when it comes to factoring in elevation, but it’s the easiest way to get a macro-level read on the weather. Find the colder pockets near you. Toggle on the cloud cover layer to find some sun coverage. Switch to the wind layer to find zones with a nice breeze. (But note wind can be a double-edged sword. In places with low humidity, there’s high risk for quickly spreading wildfire). Sometimes the patterns might surprise you. Right now, the Lake Ingalls trail is 5 degrees cooler than Navaho Pass despite the two trails being less than 10 miles apart.

- Get strategic selecting hot day hikes. It’s okay to scale back on mileage and vert. Your circulatory system is already working harder from being in the heat. During the Seattle heat wave of 2021, I planned a backpacking trip to Silver Lakes in the Olympics. It’s a third of the vert and half of the mileage that I’d typically do for a 2-day trip, but it accommodated my body and its ability to stay cool. I looked for a trail with decent shade, lots of stream crossings, and gradual gains vs. a steep climb.

- Know whether you’re at increased risk for heat illness and injury. Most heat advisory messages target major population groups – older folks, kids, people with chronic illnesses. But there is a litany of medications that affect heat tolerance. My acne meds are a diuretic that can also throw off my electrolyte balance. My old birth control raised my body temperature and active heart rate when I was first adjusting to it. A number of anti-anxiety and anti-depressants make you sweat less. Over the counter pain meds reduce blood vessel dilation or put stress on your kidneys. And then there’s also a genetic component to heat tolerance.

- Maximize evaporative cooling. Heat is used as energy to evaporate water, which makes us cooler. Our body does a lot of this on its own through sweat, but adding extra water means getting even cooler. It can be the difference between a tolerable hike and a comfortable hike. And unlike sweat, water doesn’t come with salt, oils, and bacteria-feeding protein, so you won’t feel as gross after a hot trail day. The best investment I’ve ever made was a small spray bottle from Sally Beauty, similar to this. I put it on a keychain carabiner, clip it to my waist belt, and spritz whenever I’m feeling toasty. I swap out for cold water at alpine lakes and stream crossings. Misting my neck, ears, and near my armpits helps with most since that’s where big blood vessels are close to the skin. It’s great since it’s portable to the dry, hot, exposed sections of the trail that tend to be the hottest. But it’s not the only way to use water to stay cool. Swim in your clothes at the lake. Soak a hat, shirt, or bandana in a stream. Dunk your head under a waterfall. Just be cognizant about any chafe-prone zones or clothing.

- Wear less, go loose. Two things keep you cool in the heat: 1) blood vessels vasodilate and 2) sweat evaporates off our skin. Hot weather clothing should accommodate both. Loose clothing creates less resistance to vasodilation. Skip the ultra-compressive sports bra or any clothing that leaves pressure marks. And then you want clothing that facilitates evaporation. It’s easier for sweat to evaporate straight into the air vs. through fabric. I’m usually a big fan of clothing-based sun protection since it’s more environmentally friendly, but on some hot days, I reach for the sprays and lotions so I can ditch the sleeves. For the bits you do cover, look for breathable fabrics that dry quickly, vented designs, and know that loose fitting and oversized garments allow for more airflow and create less of a hindrance for evaporation.

- Mitigate other risks. If you usually solo hike, think about taking a capable buddy. If you’re buddy’s a liability, leave’em behind (you know, the one that doesn’t eat or drink enough, struggles with sustainable pacing, or always seems to be nursing a hangover). Alone, maybe err towards trails with a little more foot traffic or ones that stay in cell phone range. Don’t scrimp on water or food.

And for a parting note, I just want to note that heat management in outdoor recreation is very “first world problems.” We’re essentially trying to maximize fun in inclement weather and the broader climate crisis. Heat might not be as dramatic as hurricanes or floods, but they’re the leading cause of climate-related deaths. American employers have zero regulations in place to protect employees from heat related injury or illness, which largely impacts marginalized workers. (OSHA’s working on new rules over the next 1-2 years, but they hinge on a consistent administration). And globally, vulnerable states with political instability or economic weakness are projected to see the most climate-related deaths. As you work to keep yourself cool, also give some thought and consideration to keeping the planet cool and habitable for others.